There are several different legal provisions that allow you to delegate the administration of your property and your health care decisions should you become unable to handle them yourself. But it’s a good idea to understand how these differ.

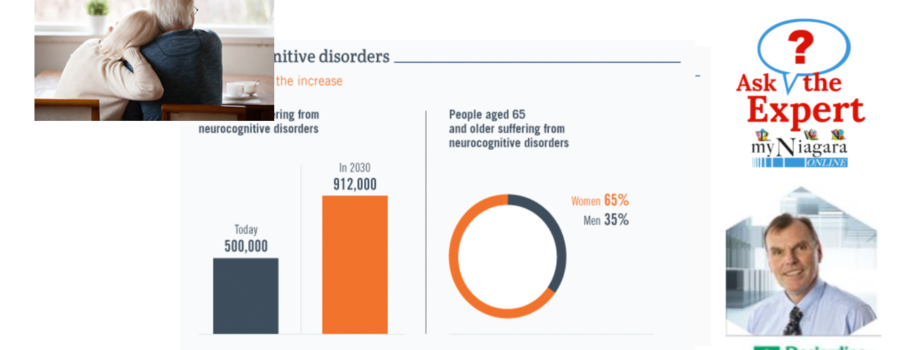

According to figures from the Alzheimer Society of Canada, no fewer than 25,000 Canadians are diagnosed with neurocognitive disorders each year. Numbers for the longer term are also revealing, as we can see here.

No matter what age it occurs, an intellectual disability can have a significant financial impact, especially if it affects someone with considerable assets or commitments. Two main forms of delegation of power could be contemplated to minimize this impact: one for property administration, the other for personal care.

1. First component: property administration

First, it’s important to specify that the law, the terms used, and the provisions that apply vary greatly from province to province. Thus, the following explanations would have to be tailored for your province of residence. Generally speaking, however, a first provision should be made for the administration of your property. In several provinces, this provision is known as a power of attorney for property. A power of attorney is a legal document by which you designate someone to act on your behalf and to represent you. This person’s powers can be general or limited to specific tasks, such as paying your bills or managing certain assets. Be aware that a power of attorney is not necessarily intended for a situation where you would become mentally incapacitated. This is why we generally talk about two specific types of powers of attorney: the “non-continuing” (or “ordinary”) power of attorney, which would be revoked if you became mentally incapacitated, and the “continuing” (or “enduring”) power of attorney, which would still apply or even be triggered by that event. Note that in Quebec a separate document, the protection mandate, must be used for loss of capacity. The protection mandate covers both property and personal care considerations.

2. Second component: personal care

To designate someone to be responsible for your well-being and your personal and health care, you need a power of attorney for personal care. Here again, the terms used for this type of provision and the associated document vary depending on the province. Generally, powers of attorney for personal care allow you to designate someone to make decisions for you in the event that you become mentally incapacitated. In particular, these decisions could relate to your housing, food, clothing, personal hygiene, health care and safety. As shown in the following graph, this person’s duties may be relatively onerous. It would therefore be important to choose carefully – which brings us to the next point.

3. How to choose an attorney or mandatary

You may designate the same person to look after your property and your personal care, or two different people. Whatever you choose, an important consideration would be to ensure that whoever you select is capable of handling their responsibilities. This means sufficient financial and tax knowledge to administer your assets, or even management skills if you own a business. You might also want to make sure that the person can perform under what could be stressful conditions and make hard decisions. Obviously, in addition to having the necessary skills, the person should be trustworthy, available and ready to accept the responsibility. If you were to designate two different people, one for property and the other for personal care, it might be a good idea to provide decision-making rules to prevent any conflict. Finally, you may establish accountability measures, which would involve reporting to a trusted third party.

4. Other documents to provide

If your instructions for personal care do not include details about your end-of-life wishes, you might want to attach a “living will” or “advance medical directives.” This document would set out what you do or do not want from your doctors in terms of end-of-life care if you are unable to express your wishes at that time. Another key document would be a record of all the information your attorneys or mandataries would need to carry out their duties: the financial services professionals and institutions you do business with, the doctors and health facilities you see for your care, etc. A will that is in order and up to date would also be valuable. Lastly, if you are a partner in a business, it could be a good idea to include provisions in your shareholder agreement in case one of the partners becomes incapacitated.

If you should suffer a loss of capacity without having a power of attorney or mandate in place, it might be the law that ends up making decisions for you through the courts. So investing a few hours to write out these provisions could be time well spent.

The following sources were used to prepare this article:

Canadian Legal Wills, “A Power of Attorney – The complete Canadian guide”.

Educaloi, “Protection Mandates: Naming Someone to Act for You”.

Get Smarter About Money, “Types of power of attorney”.

Government of Canada, “What every older Canadian should know about: Powers of attorney (for financial matters and property) and joint bank accounts”.

LawDepot, “Power of Attorney FAQ – Canada”.

Société Alzheimer, “Dementia numbers in Canada”.

Willfull, “Power of Attorney 101”.

Back to myNiagaraOnline

Back to myNiagaraOnline